Giving voice to all stakeholders in civic design: 5 questions with Anya Grant

The education market sector leader shares how to ensure everyone has a say in public projects, from universities to City Halls and everywhere in between

The design of the Alexandria, Virginia City Hall renovation included a heavy public outreach component.

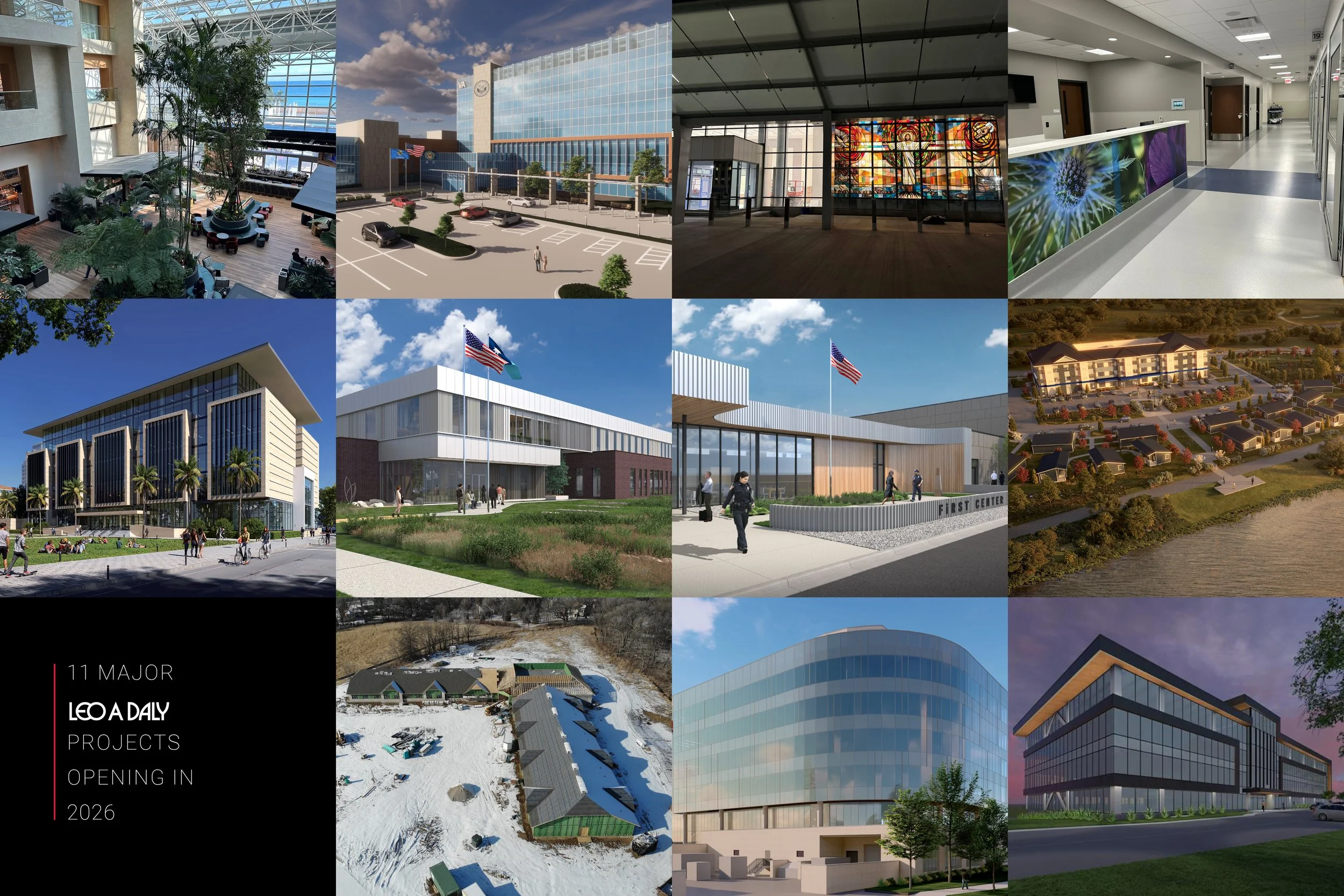

Recent Perspectives

Civic projects are all about the public. Universities, libraries, city halls: These institutions are for people, so the design should accommodate the needs of the people. While some needs are universal, each community and project has its own special relationship with the people it serves. When done right, public outreach can inform and deepen the design of a public project, making sure everyone’s voice is heard in the process. In this interview, LEO A DALY’s Anya Grant, a civic market sector leader, shares strategies for reaching into all corners of the community to gather insight.

1. Why is public outreach an important part of the design process for civic buildings?

Our projects shape public space, which means they will impact many people — the majority of whom we will never meet — for a long time to come. So we must work hard to obtain insight into how current and future users might benefit from our projects. Each place that we work in is unique. And when we effectively engage communities, we get invaluable insights into communities’ needs and desires. We want to build a space that works for everyone, and to do that we have to hear as many voices as we can.

For our clients, their core missions prioritize supporting diverse stakeholder groups. A capitol project can be a transformative investment for these groups, but only if their voices are included. This can be daunting, because not every need that is voiced can be met within the constraints of the design process. When we find natural alignments between strategic targets and individual needs, our design goals become even clearer.

2. Who are the main stakeholders in a public project? How does your approach differ for each group?

Of course, there are daily users of the building, such as staff, students or residents, who are easy for us to reach. The broader public has varying levels of investment depending on how often they visit the building or site. Very often, there are users who do not access our clients' services because of barriers that exist or who might see unintended outcomes from the project. When we meet these users where they are, we're able to evaluate possible impacts and address them with our design, making the final product a more accessible and welcoming space.

For example, at the University of Maryland’s Thurgood Marshall Hall, the obvious stakeholders are those who come there to learn and work and those that operate it. But as we worked closely with the university facilities groups, who are most in tune with campus-wide concerns, we identified areas around the building that would be transformed by its construction, and we were able to make that transformation a positive one.

For example, the marching band uses the adjacent field for practice. Working proactively with the university to identify the inherent conflict between the tuba player and the professor leading an introductory course, we performed an acoustic study that led to improved sound isolation for select windows. This would have been a costly upgrade if not identified during the design process. Another surprise set of stakeholders were transit users — a transit station was being built nearby, and the impact to existing campus pedestrian flow was significant. The resulting design is deliberately porous and provides accessible paths for those navigating the grade-change between the transit stop and campus beyond.

Thurgood Marshall Hall

3. What does a typical outreach plan include? How do you tailor that plan to address community specific challenges and opportunities?

Structure - with adaptability. We outline outreach goals with our clients and develop a timetable that allows us to reach the desired groups. This typically includes a variety of media and formats to cast a wide net.

We know some people are already engaged and will meet us where we are, but many people won’t. To engage as many people as possible, we have to go to them. This means showing up where we know they’re going to be - farmers’ markets, pop up events at local schools, holiday parties for citizens’ groups. For the very hard to reach folks, we set up a series of highly publicized online surveys, shared widely through traditional media, social media and then with QR codes on yard signs and on city buses — all methods to penetrate a range of demographics.

When we first connect, we start with listening and confirming that we understand what we’re hearing. Only then are we prepared to follow up with recommendations. Over the course of meetings with stakeholders we often learn the most effective ways to gather input and can add new strategies and streamline our approach to reflect what we've learned about how we can really get people talking.

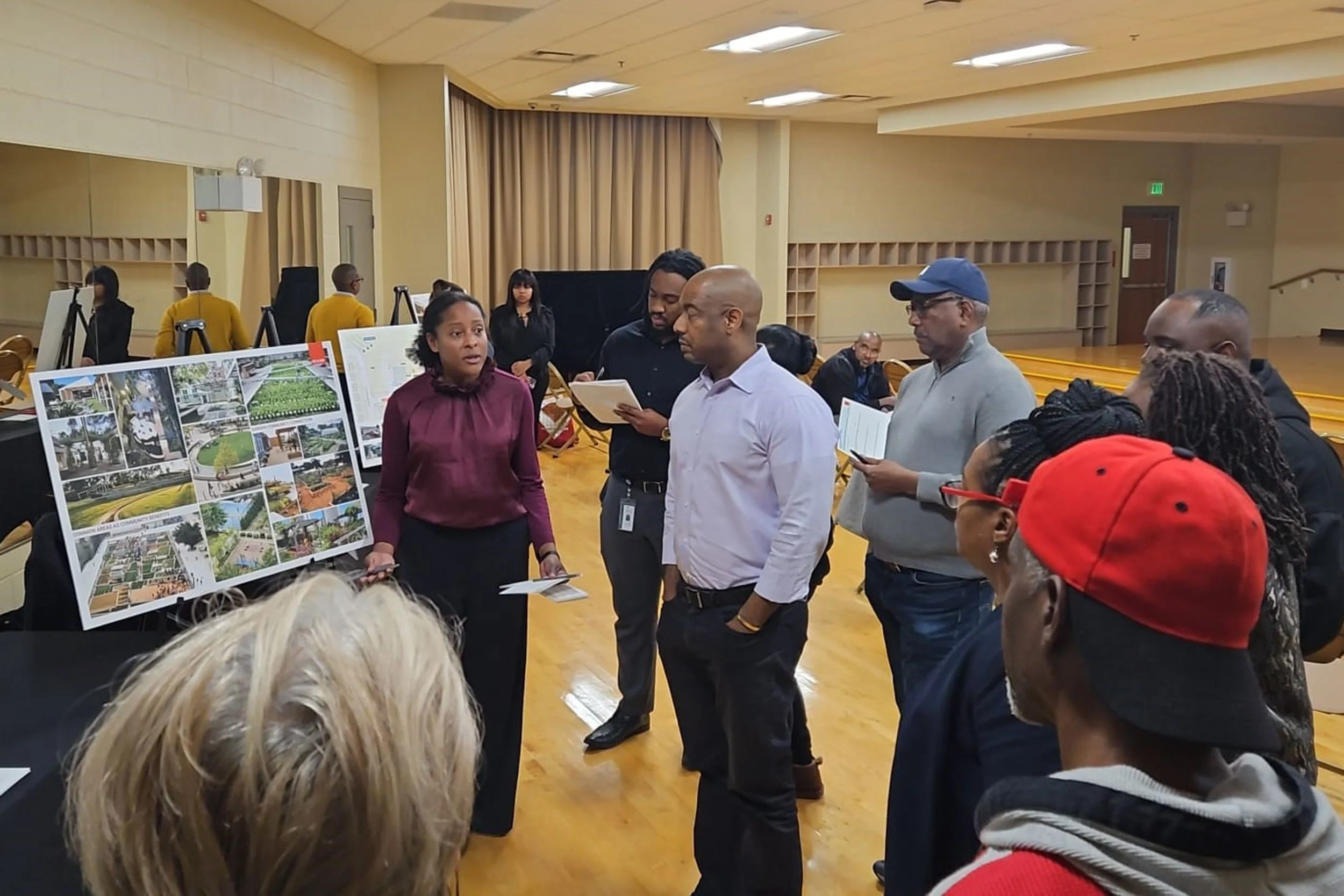

Anya Grant gathers community feedback as part of the Morgan State University historic stewardship project.

4. How do you ensure underrepresented voices are included in the outreach process?

Our approaches range from tapping into existing networks and platforms to developing content for language accessibility if there is a particular demographic that we are missing. Offering the same content through various media — in person forums and virtual channels — is key to bringing more people into the conversation.

One of the most effective ways to do this is to partner with a community group or community leader to help facilitate the discussion. This person already has an established relationship and trust with a group of people, allowing for repeated touchpoints and deeper insights. At Morgan State University, when developing its historic stewardship plan for preservation of 13 campus buildings, we partnered with a remarkable faculty member who embedded outreach work into her lesson plan. Her students were able to offer insight into the student body and alumni network. Those conversations gave us access to a broader community and shaped how we documented what was most valued by the community and therefore, most desirable to be preserved.

5. How do you incorporate public feedback into the design process?

If we've done our job of crafting engagement prompts that have actionable results and we have lots of respondents, we've created a data set that helps our clients choose between alternatives. Stakeholder input becomes one of the key considerations — like aesthetics, function and cost — that drives decision-making.

In the renovation of the Alexandria, Virginia City Hall, a lot of our public outreach related to the adjacent plaza. The area is significant to citizens as a heavily programmed hub of civic life, a meeting spot for residents, and a tour stop for visitors. In our conversations, we learned a lot about how people use the plaza — and, as importantly, who cannot use it. Although there is abundant, affordable parking in the garage just below the plaza and city bus stops directly adjacent, you currently have to climb a half story or traverse more than 200 feet to get to the front door of City Hall if you are in a wheelchair or pushing a walker or stroller, making it inaccessible to nearly anyone with any sort of mobility issues. Our design took this into consideration and seeks to provide universal access, improving the experience for residents and visitors alike.

About the author

Anya Grant, AIA

Market Sector Leader - Civic & Education

Anya Grant is a market sector leader at LEO A DALY with nearly two decades of experience in programming, planning and design for civic and educational institutions. She is recognized for her collaborative approach, engaging with all stakeholders to create master plans and innovative environments that reflect institutional and civic identities.

Anya’s portfolio includes leading projects such as the University of Maryland School of Public Policy, The Heights for Arlington Public Schools, and the Morgan State University Campus-wide Historic Stewardship Plan. Her expertise in outreach and consensus-building ensures that diverse voices are incorporated into every phase of the design process, resulting in spaces that serve both educational and public missions.